The language used to classify individuals living outside traditional housing has changed over time, reflecting shifts in social values and economic goals. Historically, terms like hobo, tramp, and bum served as descriptive types rather than simple insults. These labels identified specific relationships to work, movement, and social life.

Examining these older categories reveals how previous generations understood poverty and choice. It also shows the limits of the modern "homelessness" label, which groups very different people into one broad group. A close look at these terms exposes a complex reality that is often hidden by modern ways of framing the issue.

The hobo was a specific type of migrant worker who traveled to find jobs. These individuals were a vital part of the labor force during times of fast national growth. A hobo was defined by a mix of movement and work. They used railroads to reach areas that needed seasonal labor, such as harvests or large building projects.

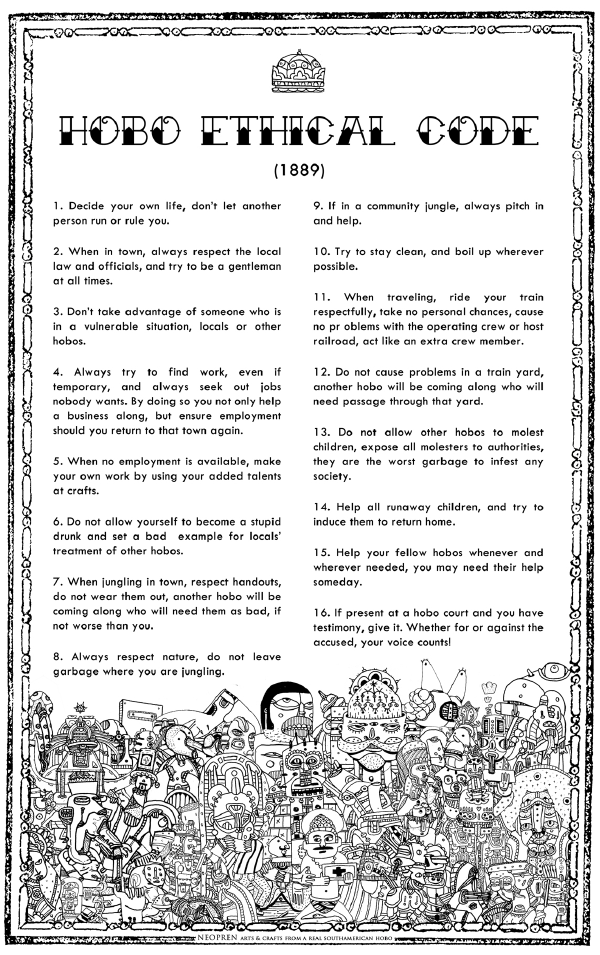

Within their own culture, hoboes followed an ethical code based on self-reliance and helping one another. For the hobo, living without a permanent home was a way to adapt to the needs of the job market. This group showed that housing instability did not always mean a person was detached from society or lacked money.

A tramp occupied a different social position, defined by constant movement without seeking work. While the hobo moved to find a job, the tramp moved to avoid one. This difference was important to the public and within the unhoused community itself. Tramps were often seen as a social problem because they withdrew from the duties of the labor market.

Still, they possessed strong survival skills and rejected the social contract that required staying in one place. The presence of the tramp challenged the idea that every able-bodied person must be tied to a specific workplace and a home. Their existence forced people to consider the limits of social control over movement.

The term bum was used for individuals who were neither mobile nor working. Unlike hoboes and tramps, bums stayed in specific urban areas, often in districts known as skid row. These individuals often struggled with chronic health issues, addiction, or the long-term effects of extreme poverty. The bum represented the most stationary and dependent part of the unhoused population. Historically, this type allowed for a better understanding of what different people needed. it recognized that a migrant worker required different help than someone with a chronic illness. This system, though often harsh, was based on observing the diverse realities of life on the margins of society.

The rise of modern homelessness as a standard term around 1980 marked a collapse of these distinct types. During this period, the diverse groups of the past were replaced by a younger and more visible population. The term homeless was adopted by the media and advocates to describe anyone without a stable home. Although this change was meant to be kind and reduce stigma, it also hid the differences between people. By grouping everyone together, the specific needs of the displaced worker and the chronically ill person were lost. This single label prevents the creation of targeted plans that address the root causes of different types of housing instability.

Vagrancy laws were the main way society controlled the unhoused in the past. These rules made it illegal to be poor and idle in public. Authorities used these laws to manage anyone seen as a burden or a threat to social order. A person found without a job or an address faced arrest and might be forced to work.

Author Jack London wrote about being jailed for vagrancy in 1895. He served thirty days for the act of being mobile and unhoused. These laws were more than just concerns about poverty; they were used to control groups that threatened the status quo. The criminalization of the unhoused has long served as a way to enforce social conformity.

The concentration of people in skid row was a physical sign of a broken social contract. These neighborhoods became the places for those who could no longer compete in the labor market. Being found in skid row was often enough to lead to an arrest. Public perception focused on disorder, leading to demands for police action to remove the poor from sight. Relying on law enforcement to manage social failures became a standard part of city life. This approach failed to fix the causes of poverty, focusing instead on hiding the problem to keep the public comfortable.

Current laws still punish actions like panhandling and sleeping in public. While the police have less absolute power than before, the demand for order remains strong. Many people value the clean look of public areas over fixing the causes of housing instability. As a result, most modern responses rely on the criminal justice system. This creates a cycle where people are moved from place to place without finding stability. A real solution requires a response to disorder that goes beyond police action. A smart plan must keep the public safe while also protecting the dignity and rights of the unhoused.

The shift in the unhoused population during the 1980s also brought more women and families into public view. New terms emerged to describe these visible groups, such as bag ladies. This visibility led people to rethink existing shelter systems. Advocates used the "homeless" label to create a sense of national urgency, framing the crisis as a tragedy needing a federal response. While this effort helped get funding for emergency services, it also reinforced the single label used today. The focus shifted from understanding the different paths into homelessness to managing a single, large problem.

Modern systems often ignore the personal choices involved in some types of housing instability. Some people may still choose a nomadic life like the hoboes of the past, while others face major barriers. Using the same word for a voluntary traveler and someone in a mental health crisis makes it harder to create good policy. An accurate framework would recognize these differences, making it easier to build support systems for each group. The failure to distinguish between economic loss, chronic illness, and choice results in a system where resources are misplaced and people are underserved.

Protecting material dignity requires moving beyond simple labels and punishment. It requires providing basic resources like hygiene, health care, and job support in a way that respects personal choice. A person traveling the country for work needs different help than someone staying in one place due to illness. Using the lessons of historical types helps in building a better system of support. This modern approach should focus on helping people gain control of their lives rather than just managing their presence. It must also address the community's concerns about how public spaces function.

History shows that using the police to manage poverty does not work. Vagrancy laws and skid row only made the poor feel more isolated. The modern challenge is to create a social contract that includes everyone. This requires a commitment to seeing the truth of life on the margins without using broad, simple labels. It requires listening to the stories of those who actually live on the streets. Solutions must be built from the real experiences of different groups. Moving past broad categories and punishment is the only way to honor the dignity of all human beings.

The names used for the unhoused reflect changing social values. While old labels like hobo, tramp, and bum were often judgmental, they were also precise. The move to use one word, homelessness, was meant to be kind, but it also created new issues by hiding the diversity of the population. To solve the current crisis, a more detailed view of housing instability is needed. Systems must be built to provide paths toward independence and inclusion. The history of hoboes, tramps, and bums shows that human spirit is strong. A just society builds the support needed for that strength, no matter how a person lives.

Future policy must use historical lessons about the link between movement and work. By creating local hubs of support, it is possible to help people maintain their rights while staying connected to the community. These centers should do more than just offer a place to sleep. They should provide job training, health services, and social connections. This model recognizes that every person has a unique set of needs and a potential to help society. Moving away from a police-led response to disorder allows for a more humane urban world. This change is the next necessary step in building a national strategy for material dignity.