If you are young, on your own, and watching rent consume half your paycheck while homeownership feels like a fantasy from another era, you are not imagining the difficulty. The economy has fundamentally shifted. What your parents could do at your age—buy a house, pay off college in a few years, expect stability—is structurally unavailable to most people now. The median age of first-time homebuyers has climbed from 28 to 38 in a generation. Nearly half of people your age live with parents not by choice but by necessity. This is not personal failure. This is the landscape.

The question becomes: how do you live sanely and meaningfully when everything feels temporary and nothing feels secure? This guide offers practical, reality-based approaches for people navigating this alone.

Redefine What Security Means

The old model equated security with possession: a house you own, a stable job with a pension, a savings account that grows faster than inflation. That model is broken for most people under forty. Clinging to it as the only definition of success guarantees frustration.

Security in a fluid economy looks different. It means continuity of purpose and adaptability of skill rather than permanence of position. Ask yourself: what endures when everything else changes? Often, it is your craft, your reputation for reliability, your network of people who trust your work. These are the new assets. A person with three income streams and portable skills has more real security than someone with one seemingly stable job that could evaporate in a corporate restructuring.

Build skills that transfer across industries. Learn to write clearly, manage projects, understand basic accounting, communicate effectively. These meta-skills protect you when specific jobs or entire sectors collapse. Your security comes from what you can do, not from what you currently have.

Shrink the Scale of Control

Global economic systems, housing markets, interest rates, and inflation are beyond your personal control. Obsessing over them drains energy you need for what you can actually influence. This is not about ignoring reality. It is about directing effort where it produces results.

Focus on your immediate environment. Clean your space thoroughly. Cook real meals instead of ordering delivery. Fix something broken instead of replacing it. These small acts of tangible work restore a sense of causality: I act, something improves. That is the seed of agency. Research on internal locus of control—the belief that your actions influence outcomes—shows it correlates strongly with resilience, lower depression, and better health outcomes even in difficult circumstances.

Every time you improve something directly within your reach, you train your brain that effort matters. This is not self-delusion. It is accurate recognition that while you cannot control the economy, you can control your corner of it.

Financial Survival Without a Safety Net

If you have no family to fall back on, every financial decision carries higher stakes. Here are non-negotiable practices:

Housing: Do not spend more than 30 percent of your income on rent if you can possibly avoid it. This might mean living with roommates longer than you would prefer, choosing a less desirable neighborhood, accepting a smaller space, or commuting further. The freedom that comes from not being rent-burdened outweighs the discomfort of a shared bathroom. If you are paying 40 to 50 percent of your income in rent, you have no buffer for emergencies, no ability to save, and constant financial anxiety that undermines everything else.

Consider non-traditional arrangements: house-sitting, caretaking properties in exchange for reduced rent, subletting during travel seasons, or joining cooperative housing if available in your area. Stability matters, but so does financial breathing room.

Debt: If you carry student debt or credit card balances, understand that minimum payments keep you trapped. Focus every available dollar beyond survival expenses on the highest-interest debt first. This is mathematically optimal and psychologically clarifying. Debt is not moral failure, but it is a chain that limits your choices. Breaking it becomes a priority that justifies temporary discomfort elsewhere.

Do not take on new debt for anything except genuine emergencies or investments that provably increase your earning capacity. The momentary relief of buying something on credit becomes months or years of reduced freedom.

Income: Assume your primary income source is temporary. This is not pessimism; it is realism. Build at least one secondary income stream, even if small: freelance work in your field, a skill you can monetize (tutoring, repair work, design, writing), selling items you create, or gig work that fits around your main job. When your primary income disappears or becomes insufficient, the secondary stream prevents total collapse.

Track every dollar you spend for at least one month. Most people hemorrhage money on subscriptions they barely use, convenience purchases, and habitual spending they do not notice. Awareness creates choice.

Emergency fund: Save obsessively until you have one thousand dollars in an account you do not touch except for genuine emergencies. Then build toward three months of bare-minimum expenses. This is your psychological foundation. Knowing you can survive a sudden job loss or medical expense without immediate catastrophe changes how you move through the world.

Cultivate Interdependence

The myth of the self-sufficient individual collapses under modern economic volatility. No one makes it alone, regardless of the stories they tell. Small circles of mutual help provide the social security that property and pensions once symbolized.

Build these relationships intentionally. Find three to five people—neighbors, coworkers, friends, members of a faith community or interest group—with whom you can exchange practical help. Watch someone's apartment or pet. Trade skills: you help with their resume, they help you move furniture. Share bulk groceries. Lend tools. Create a small lending pool where everyone contributes twenty dollars a month and members can borrow interest-free in emergencies.

These networks require vulnerability. You must ask for help and offer it before you feel comfortable doing so. The discomfort is the price of the safety net. People who operate in mutual aid circles weather financial shocks that would destroy isolated individuals.

If you lack local connections, start small. Attend events related to your interests. Volunteer for organizations doing work you respect. Join online communities focused on practical skills rather than passive consumption. Show up consistently. Relationships form through repeated low-stakes interaction more than dramatic moments.

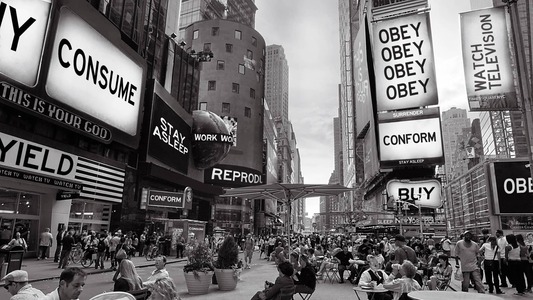

Detach Identity From Economic Status

Inflation, stagnant wages, and debt can distort your sense of self-worth. You will be tempted to measure your value by your income, your housing situation, your ability to afford what others seem to have easily. This is a trap that leads to either despair or debt.

Recognize that being valuable and being valued in the market are not the same thing. You can produce meaning, kindness, insight, beauty, and help—none of which depend on currency. Some of the most meaningful work pays poorly or not at all. Some of the highest-paid work contributes nothing lasting.

This does not mean money does not matter. It does. You need enough to survive and enough to stop obsessing about survival. But once you have sufficiency, additional money provides diminishing returns on actual life satisfaction while requiring increasing sacrifices of time, energy, and autonomy.

Define success by what you build, what you learn, what you repair, and who you help rather than what you own or earn. This is not spiritual platitude. It is practical psychology. People who derive identity primarily from economic status experience more anxiety, more volatility in self-worth, and less resilience when markets shift.

Build Memory and Continuity

In a world where you might move frequently, change jobs every few years, and lack the physical anchors your parents had, memory becomes your foundation. Keep a record of your life—a journal, a digital document, voice memos, anything that captures your experiences, lessons learned, and relationships that mattered.

Write down what you figured out the hard way so you do not have to relearn it. Document friendships even as they shift. Record small victories: the first time you fixed something yourself, the day you paid off a debt, the moment you helped someone else navigate something you had just survived.

This practice serves multiple purposes. It creates continuity across transitions. It provides evidence that you are not static, that you have grown and adapted before and can do so again. It honors relationships even when physical proximity ends. People who remember and are remembered never quite drift away.

Practice Temporal Humility

Understand that instability is not only decline. It is also the natural process of one era yielding to another. The economic arrangements that feel permanent to one generation dissolve for the next. This has happened repeatedly throughout history. Many before you lived through equally uncertain shifts and found ways not just to endure but to build new forms of stability appropriate to their conditions.

You are not experiencing the end of possibility. You are experiencing the gap between an old system that no longer functions and a new system that has not yet fully emerged. This gap is uncomfortable, sometimes frightening, but it is also where creativity and adaptation happen.

Seeing yourself within that long arc softens panic and reintroduces patience. The choices you make now—the skills you build, the relationships you cultivate, the financial habits you establish—are laying groundwork you may not see the results of for years. That is normal. Most meaningful things take longer than our culture pretends they do.

Rebalance Effort With Being

When honest effort seems not to secure anything permanent, shift your effort toward expression rather than accumulation. Make music, write, repair things, mentor someone younger, create anything that completes itself in the doing rather than requiring external validation or compensation.

This is not distraction from financial reality. It is protection against despair. The product may fade, but the act itself is complete. You wrote the essay. You fixed the bicycle. You taught someone a skill. These actions have inherent value regardless of whether they produce income or lead somewhere obvious.

Balance pragmatic survival work with work that feeds something deeper. Both are necessary. One pays bills. The other reminds you why staying solvent matters in the first place.

The Practice of Sanity

Living sanely in uncertain times is not about achieving security as previous generations defined it. It is about building portable forms of stability: skills that transfer, relationships that endure, practices that create continuity, and identity grounded in what you do and who you help rather than what you own.

You cannot control the economy, but you can control your response to it. You cannot eliminate uncertainty, but you can develop capacities that make you resilient within it. You cannot guarantee permanence, but you can create meaning that does not depend on it.

The work is unglamorous: tracking expenses, learning skills, building networks, cooking meals, keeping records, showing up for people, choosing deliberately rather than drifting. But this work compounds over time into something that feels like ground under your feet even when the landscape keeps shifting.

You are not failing because you lack what your parents had at your age. You are adapting to different conditions, building different forms of security, and learning different definitions of success. That adaptation is not consolation. It is the actual work of your generation.