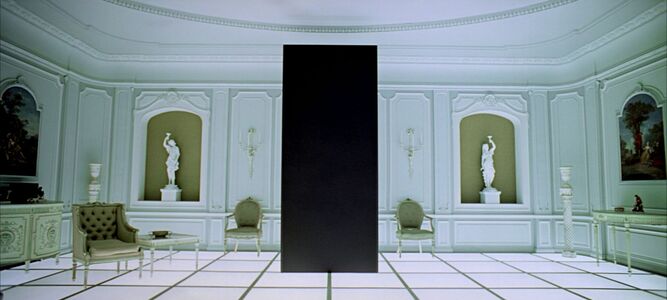

The historian of 2226 opens archives from two centuries prior and finds a curious phenomenon. The people of 2025-26 believed their moment was unprecedented. They described their conflicts as uniquely intense, their divisions as historically deep, their technological disruptions as fundamentally different from anything that came before. They were simultaneously correct and entirely wrong.

Every generation experiences its crises as unique. The emotional intensity feels specific to the moment. The stakes appear higher than ever. The people of 2025-26 were not unusual in this belief. What makes their period interesting to future study is not uniqueness but rather how perfectly it demonstrated patterns that recur across centuries.

The invisible pattern was that institutional failure appeared as discrete events to contemporaries. A scandal here, a policy failure there, declining trust in particular organizations. Each incident seemed to have specific causes: poor leadership, partisan opposition, technological disruption, or economic stress. Observers diagnosed those problems in terms of immediate visible causes.

From a longer vantage, the pattern becomes obvious. Institutions were not failing individually due to isolated causes. They were collectively entering a predictable phase of their lifecycle. Institutions built in the mid-twentieth century had reached a stage where their operating assumptions no longer matched conditions. They attempted to solve problems using frameworks designed for different circumstances. This mismatch appeared to citizens as incompetence or malice when it was actually structural obsolescence.

The technology question centred on governance rather than capacity. Citizens of 2025-26 argued over artificial intelligence, social media, and surveillance. Debates focused on whether technology was good or bad, whether it should be controlled or liberated. These framings assumed technology acted as an independent force. They missed that technology is capacity: tools deployed according to who controls them and what goals they pursue.

The era's central question was who decides what these capacities do and for what purposes. Framing debates technologically avoided examining power structures. This omission allowed capacities to increase while accountability and decision-making authority did not democratise. The danger was not that artificial intelligence would become independently dominant; the danger was that existing power structures acquired new capacities without new accountability.

Polarization became the central phenomenon, not the content of disputes. Citizens organized into opposing camps. Each camp believed it defended civilisation against existential threat. The conflict appeared to be about specific policies and values. Future historians see that the structure of perpetual conflict mattered more than particular positions. Both sides required an opponent to sustain identity and purpose; without an opponent, tribal identity dissolved. This created incentives where resolution threatened tribal cohesion and continued conflict became stabilizing.

People devoted enormous resources to symbolic action. Street protests, social media arguments, news consumption, and political campaigning absorbed billions of hours and trillions of dollars. These activities produced emotional satisfaction and reinforced identity. They rarely changed policy or institutional behaviour.

Meanwhile, activities likely to produce durable change received little attention. Learning institutional procedures, building alternative structures, developing practical skills, creating mutual aid networks, and establishing independent systems required sustained effort without immediate reward. Few pursued these paths because the incentive structure rewarded performative action. The aggregate effect was massive energy expenditure with minimal strategic result.

Temporal distortion compressed decision horizons. Political cycles ran on two- or four-year intervals. Business planning rarely passed five years. Individuals planned little beyond a decade. Within these timeframes, every problem appeared urgent and every crisis existential. Short horizons discouraged long-term investment in solutions that might take decades to mature. They encouraged tactics that yielded immediate results even if they worsened long-term outcomes.

Lists of contemporaneous fears make fascinating study material. People worried about elections, particular policies, individual leaders, and immediate economic indicators. Most of these fears proved less consequential for the long-term trajectory than deeper structural factors. What mattered more was the rate of institutional decay, the speed of technological capability expansion, the distribution of critical resources, the resilience of essential systems, and the formation of new organising principles that would replace failed institutions.

Future historians identify one question rarely asked in 2025-26: what if the conflict itself is the problem rather than any particular side winning? Asking that question required stepping outside tribal frameworks and abandoning social belonging and moral certainty. Few were willing to pay that price. The question was suppressed because it threatened the structures providing identity and purpose.

Multiple futures remained possible from the vantage of 2026. Institutions might reform and regain legitimacy; they might collapse and be replaced; technology might democratise power or concentrate it further; polarization might deepen into violence or exhaust itself. Uncertainty was real. Those who acknowledged uncertainty while acting according to their values operated more honestly within constrained knowledge.

Not everything from 2025-26 disappeared. Some institutions adapted. Some technologies proved beneficial. Some communities maintained continuity. The things that survived shared characteristics: they solved real problems rather than providing symbolic satisfaction; they adapted to changing conditions rather than defending fixed positions; they served genuine needs rather than institutional self-preservation; they operated on principles durable across changing circumstances.

Many insights about 2025-26 were available to contemporaries. Historical precedents existed and pattern recognition was possible. What was lacking was incentive to act on that knowledge. Those who identified lifecycle patterns were ignored. Those who advocated long-term resource allocation were considered impractical. A few built alternatives and were treated as fringe actors.

The historians of 2226 face their own version of the same challenge. They see clearly what their predecessors did not. They possess information unavailable at the time. This creates an illusion they would have acted differently. They too face institutional transitions and social fragmentation. The value of studying 2025-26 is not moral superiority; it is recognising recurring patterns and identifying common failure modes.

From the vantage of 2226, 2025-26 appears as a hinge point. Conditions constrained which pathways remained accessible: some possibilities closed, others opened. The actual path emerged from countless choices made without full knowledge of consequences. The most valuable insight future historians might offer contemporary readers would be simple: the moment is both less unique and more significant than it feels. The patterns are old; the stakes are real. Neither certainty nor despair serves well. The future remains contingent on choices not yet made.